Nemo me impune lacessit *

Although by 1066 the boundaries of Scotland were established, they were by no means secure. From

the north and west, the Norse had long been making inroads. From the south, England began to cast

covetous eyes northward. Over the next three centuries the struggle to maintain its independence

would consume all the nation’s energies.

At the start of the millennium, Norway claimed the Shetlands, Orkneys and Hebrides and enforced

those claims whenever it had a strong ruler. When it didn’t, local Jarls were only too quick to make their

own claims. In the end, the loosening of the Norsemen’s grip came, not from the crown, but from a half

Norse, half Scot named Somerled who carved out his own petty kingdom in the Western Isles and

mainland.

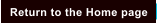

From the mid 1100’s Somerled expanded

his rule to stretch from the Isle of Man

north to the Butt of Lewis. The Lordship

of the Isles contained a mixed people of

Norse and Scottish blood, sharing under

one lord, a single culture and way of life.

Known as the Gall-Gaidheal (literally

meaning 'Foreign-Gaels') they came to

dominate the West of Scotland with their

influence centered on the swift galleys

from which they enforced their rule. The

islands and sea-lochs of the west of

Scotland gave the advantage to a

maritime power over the land-based

sovereignty of the Scots kings. Not only

were the islands separated by the sea but

the deep intrusions of the sea lochs and

rugged mountains meant travel by land

was three to five times as far as a galley

could sail. And galleys sailed faster than the land traveller,

Following Somerled’s death in battle against the Scottish crown, the Lordship of the Isles would be the

source of struggle for centuries and, although absorbed by Scotland, the loyalty of its inhabitants

would remain in question for centuries; until 1745 at Culloden when Bonnie Prince Charlie led the

Highland clans to defeat in the last battle on British soil.

The Orkneys and Shetlands would pass more peacefully into Scottish possession.

Though the north and west might take centuries to fully secure, the real threat was from the south.

Here a more numerous and powerful neighbour looked to annex Scotland’s land and peoples. It would be

a long hard struggle and bleed Scotland all but dry. Yet despite the disparity in strength and the Scots

many defeats, England would eventually recognise that the Scots were never going to accept conquest.

In the end, it was the peaceful ascension of the Scot's king James VI to the English throne that would

bring an end to the wars.

After Malcolm had redefined the Scottish border by absorbing the Lothians and securing the Border

region against Anglo-Saxon domination, a new enemy appeared that was to both strengthen and weaken

Scotland. These were the Normans. Led by William of Normandy they conquered England in 1066 and

reinvented government. Apart from some trials of strength on their part and a couple of abortive

attempts by the Scots to take advantage of the upheaval, William was content with the major prize.

The transformation in England also brought changes to Scotland. Edgar the Atheling or Saxon claimant

to the English throne sought sanctuary at the court of Malcolm Canmore. Malcolm, a recent widower,

became enamoured with Margaret, Edgar’s sister and the two were wed. Under Margaret’s authority,

the religious scene in Scotland changed with the influence of the Celtic church giving way to that of

Rome. Anglo-Saxon English thrived (even today the Scots dialect more nearly mirrors Old English than

does any in England itself). Trade and culture were also affected by a court with such a high Saxon

profile.

The other effect caused by the conquest of England was the gradual absorbsion of Norman knights into

the Scottish nobility and Norman clerics into the church. Much of this was due to the English demand

for hostages after a series of minor wars between the nations, generally settled in England’s favour.

One after another, the heirs to the Scottish throne were brought up in the English court, making

friends and allies amongst the Norman ruling class. When, eventually they returned, they brought with

them to the north their own entourage. Later, as rulers, they would reward past favours with titles,

either outright or by marriage to heiresses they held as wards. The net effect of this Norman

influence was to strengthen the central government and the role of the church and further undercut

the Celtic administrative and social structure.

For two and a half centuries, from the mid 1000’s to the end of the fourteenth century, Scotland was

relatively peaceful; at least compared to the years to come. The English made no serious attempt at

conquest and the Scots crown gradually extended its authority over the land.

Everything then changed, in 1286 King Alexander III died tragically by accident leaving only a young

granddaughter brought up in a foreign land to inherit the kingdom. All might have been well; an

arrangement had been made to betroth her to the heir to the English throne with the guarantee of the

independence of Scotland. This would certainly have assured the peace of Scotland, at least in the

immediate future. But it was not to be, Margaret, the Maid of Norway, died on her way home to

Scotland.

The scene was now set for the crisis that was to all but consume Scotland over the next half century.

With the direct line ended, there was no lack of claimants to the throne. Meanwhile, with the

uncertainty of the succession looming, King Edward I of England now began to look at Scotland as a

plum, ripe for the taking.

Of the claimants to the throne, the two strongest suits were those of John Balliol and Robert Bruce.

The enmity between those two factions caused disharmony amongst the Scots and played into the

hands of Edward. In the end Balliol was chosen, with the complicacy of the English monarch. That Bruce

also had sought Edward’s support shouldn’t be forgotten, but the upshot was that Edward now

insisted that the king of Scots owed fealty to the English crown.

This overlordship claimed by Edward did not sit well with many Scots and it wasn’t long before war

resulted. The disillusionment and disharmony amongst the Scots showed itself in the subsequent

debacle of the defeat of the Scottish army at Dunbar. With the Scots loss in battle and no unity to

oppose him, Edward quickly conquered Scotland. Balliol was forced to abdicate and removed as a

prisoner to London. In ten years, Scotland had gone from a strong secure independent nation

to but a province of England.

But Scotland wasn’t finished. The great lords had all sworn fealty to

Edward but from the ranks of the lesser gentry came William Wallace

to reignite the national spirit. He wasn’t alone, many ordinary Scots

flocked to him but the nobility in the main held back. A few nobles,

including Robert Bruce, son of the Robert Bruce who had contended

for the crown joined the struggle in what was at best a half-hearted

effort. Bruce was not yet ready for the kind of warfare the struggle

for Scotland’s survival required; he still thought of war in terms of

formal battles and chivalry.

Wallace, though, was every bit a practical soldier and as innovative as

Hannibal. He organised his army into what became known as schiltroms,

soldiers armed with spears or pikes , protected by shields and arrayed

in “hedgehog” formations. He generally avoided face to face

confrontations with the superior English and carried out a guerilla-like campaign. One great exception

was the battle of Stirling Bridge where he annihilated an English army by allowing half to pass over the

only bridge to the town of Stirling before rushing in to cut off reinforcements from the opposite bank.

It was a great victory but not the end of the war.

After Stirling Bridge, Wallace was forced on the defensive by the reinforced English invaders. Finally

he was betrayed by his own countrymen and suffered ignominious death at the hands of the English.

The Bruce had not only English enemies to contend with but the supporters of the abdicated king Balliol,

most notably the Comyns. In a series of campaigns against the Comyn’s and their supporters, the Bruce

Thus it was in 1314 that the largest ever army to invade Scotland made its way north. The Bruce

gathered together his army and, following the course Wallace had established, withdrew in front of the

English leaving a wasteland to his enemies. At Bannockburn, where the Firth of Forth may be forded and

just a few miles from Stirling, he prepared for battle on ground of his choosing.

The English arrived in the evening and in one famous encounter, Sir Henry de Bohun, arriving ahead of

the vanguard recognizing the Bruce, alone in front of the Scottish positions, charged. King Robert,

unarmoured and mounted on just a palfrey darted

out of the way of the lance and killed de Bohun with

a blow from his axe. It was a good omen for the

Scots.

That night the English, faced with the marshy

ground in front of the Scottish positions, were

forced into scattered and uncomfortable camps

wherever some semblance of dry ground might be

found.

The next morning, Edward II, eager to get to grips,

committed the English before a proper plan and

organization had been arrived at. Thus, though

greatly outnumbered, the Scots gained an initiative, able to use the ground to their advantage and deny

the English the full use of their superior cavalry. The Scottish schiltroms held and gradually ground

down the English charges. In the end, Edward fled ignominiously.

Bannockburn, although a decisive battle that secured Scotland for the time, was not to be the end of

the English threat. But it did put an end to any real chance of Scotland’s annexation. It gave the Bruce

the security to reestablish the nation, to rebuild and strengthen.

to be continued .........

To Return to the Main Scotland Page

To Return to my Home Page

established a firm control of the land. All that were left were

some few castles in English hands. It was to one of these that

Edward Bruce, Robert’s brother made a chivalrous but foolish

agreement; should Stirling castle not be relieved within a year

then the castle would be surrendered. This was foolish in that

it forced the English hand and a new campaign was organized

to save the castle; Edward II could not afford to meekly let

it go.

Sir William Wallace